Breguet – Year Of The Tourbillon

Ask any true fine watch aficionado to name the aspects of mechanical watchmaking they find most fascinating, and the tourbillon will almost certainly always make its way onto the list. Visually mesmerising and technically brilliant, this exquisitely complex mechanism sits at the pinnacle of haute horology. The tourbillon is more than just a mechanical work of art though. It is the result of a precise study of physics, a commitment to innovation and an unrelenting drive to achieve ever greater precision.

This year marks the 220th anniversary since Abraham-Louis Breguet (1747–1823), one of history’s greatest watchmakers, patented his singular invention. Today, it has been adopted by a number of other watchmaking brands and become something of the gold standard in fine watchmaking. It holds a particularly special place, however, at the House of Breguet, its custodian. In 2021, the brand will further commemorate its founder’s ingenuity, and the treasure that is the Tourbillon, through various events and the celebration of a new model on June 26. Before that though, it’s well worth taking a few moments to explore the origins of this eye-catching complication.

The Watchmaker

By the time he began working on the invention of the tourbillon, Abraham-Louis Breguet was already a very well-established and highly successful watchmaker. Having begun his apprenticeship at the age of 15, he travelled from his home in Switzerland to France, where he received a formal academic education at Paris’ famed Mazarin College (also known as the College of Four Nations). This gave him a strong grounding in the sciences, particularly mathematics, helping him develop the engineer’s mindset that would enable him to later thrive as one of history’s most innovative and pioneering watchmakers.

After completing his apprenticeship, he went on to set up his own business on Île de la Cité in 1775. Countless technical innovations would follow, each presented in Breguet’s trademark sophisticated yet minimalist style. Such was his ingenuity and creativity that he soon built up an enviable list of patrons, including King Louis XVI – who was particularly taken with the self-winding watch Breguet created for him – and Queen Marie-Antoinette, along with many leading public figures and members of the European nobility. In a matter of years his name became known in all the major capitals, with many aspiring watchmakers seeking to emulate his techniques.

His association with the royal court however meant that in 1793, Breguet was forced to flee the excesses of the French Revolution and seek refuge in the country of his birth. He lived in Switzerland for two years, first in Geneva, then in Neuchâtel, and finally in Le Locle. In typical fashion Breguet made good use of this time away, engaging in period of intense intellectual work and exchange with the Swiss watchmakers of the Geneva and Neuchâtel Jura regions. Upon his return to France in the spring of 1795, his various observations lent a spectacular new lease on life to his career.

During the five years following Breguet’s return to Paris, the Maison unveiled a number of novelties, including the tactile watch (which allows time to be read by touch), the Sympathique clock (which resets and synchronizes watches placed on top of it), the subscription watch (highly regarded for its minimalism), a new constant-force escapement, and a new mechanism referred to as a “Tourbillon regulator.”

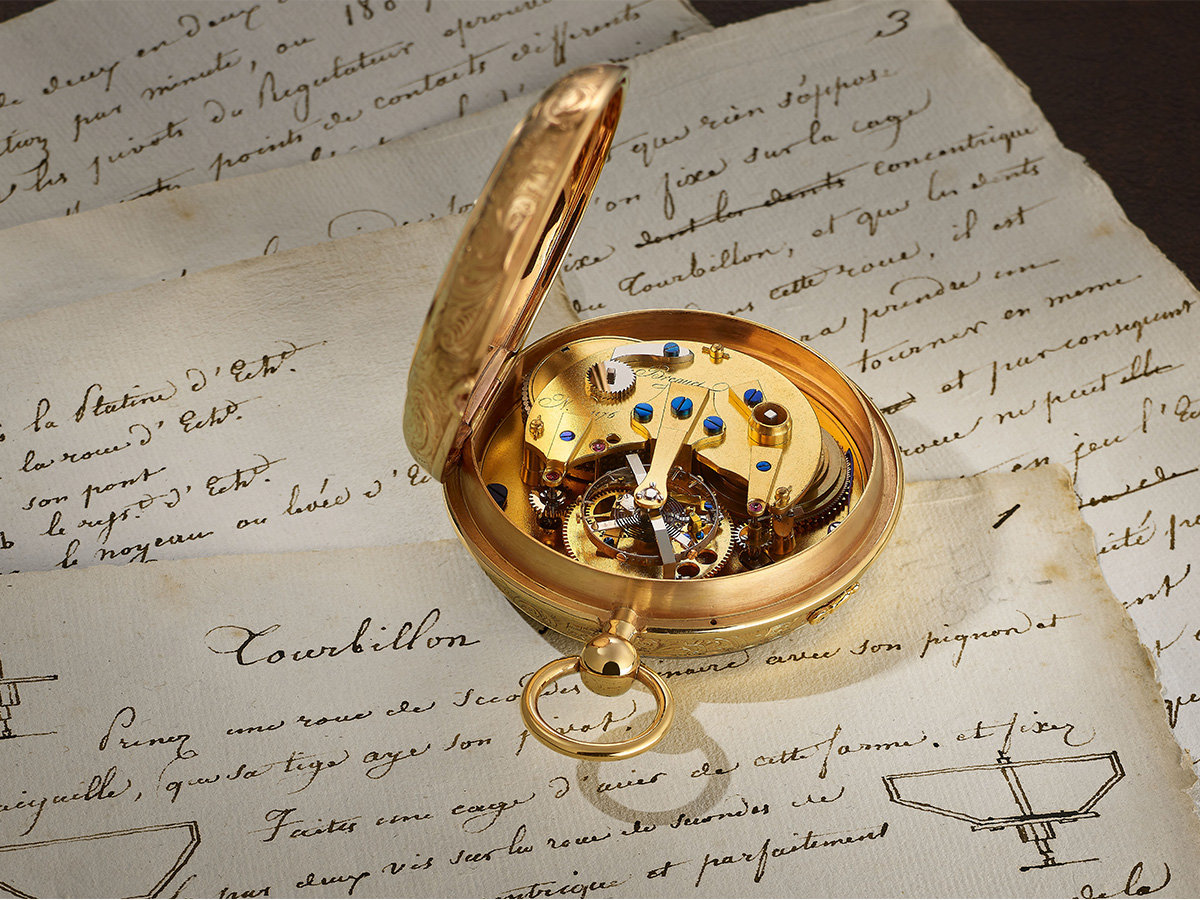

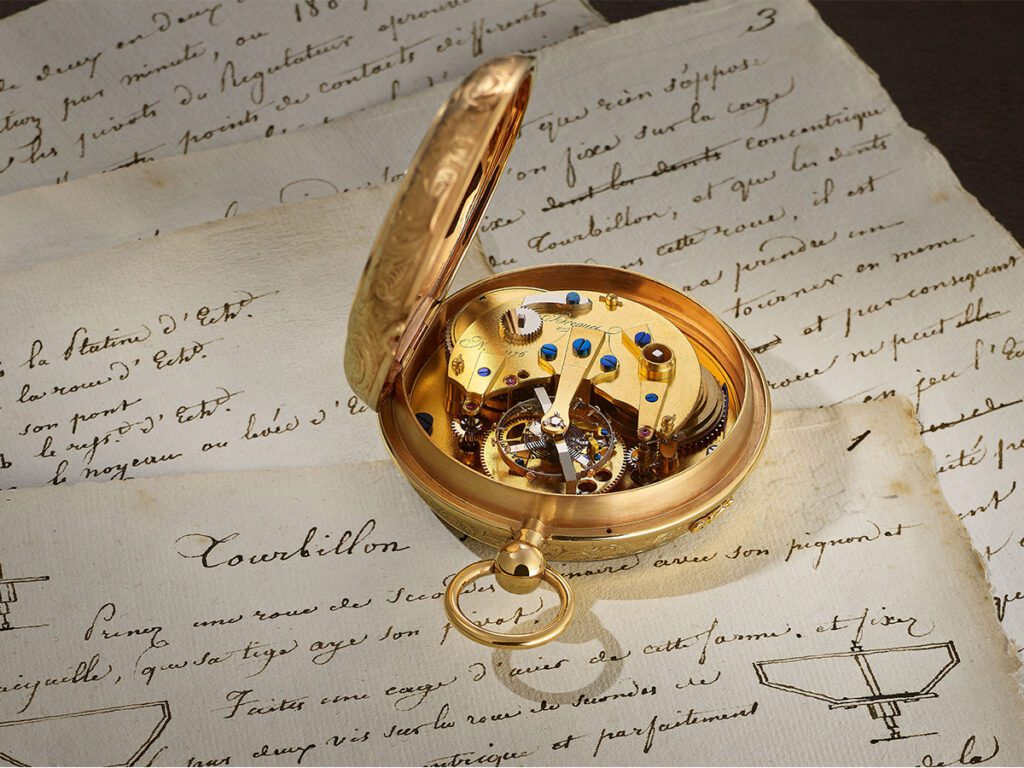

The Tourbillon

Through intense study and observation, Breguet had perfected his understanding of the factors – especially those affecting the escapement – that might impair the precision of a timepiece. The pocket watches of the time were particularly susceptible to the influences of gravity – and the negative consequences this entailed – because they often spent long periods in one position. Realizing that he would not be able to solve single-handedly all the problems associated with the expansion of metals and the stability of oils, Breguet coped with those issues by working around them. He “compensated” for the effects of the laws of physics that affect the inner workings of a watch and, with them, its rate regularity.

To do this, he conceived the revolutionary idea of mounting the escapement and balance wheel inside a rotating cage in order to negate the effects of gravity when the timepiece was stuck in one position. By continuously rotating the entire balance wheel/escapement assembly at a slow rate it would be theoretically possible to average out positional errors. That was the theory, anyway. Perfecting this complex mechanism was anything but a straight-forward process.

Assuming that the idea for the Tourbillon took root in Breguet’s mind between 1793 and 1795 (during his time in Switzerland), its realization then took six years, from his return to Paris until the patent on June 26, 1801 was obtained. It then took another six years for sales to pick up. This suggests that Breguet had likely underestimated the difficulties of fine-tuning this new type of regulator. Thus, he dedicated over a decade of his life to developing his extremely complex invention and making it reliable. He praised it as a mechanism, which allowed timepieces to “maintain their accuracy, irrespective of whether the position of the watch is upright or tilted.”

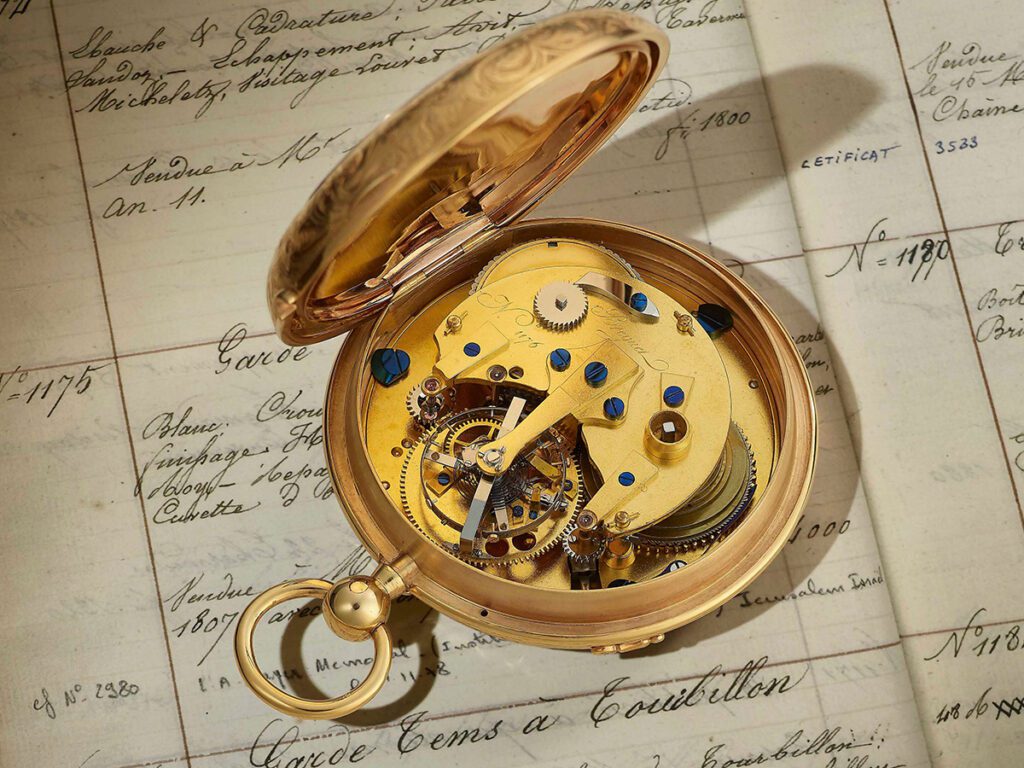

Convinced of the significance of the invention, which could be installed in different types of timepieces, Breguet and his staff went on to produce 40 Tourbillons between 1796 and 1829 – plus nine other pieces which were never finished and appeared in the ledgers as written-off, scrapped or lost. As you might expect a number of these ended up in the personal collections of Breguet’s well-heeled clientele. But what is perhaps more interesting is that roughly a quarter of these tourbillon-equipped timepieces are thought to have been used for naval purposes, i.e. for navigation at sea and for calculating longitude. An explorer in Africa used the watch for the same purpose. Closer to home, Thomas Brisbane reached Australia with his. Some pieces were used on the global ocean for half a century. Several pieces even belonged to leading scientists. Clearly, and in line with Breguet’s own classification, the Tourbillon fell into the category of watchmaking for scientific use rather than watchmaking for civilian use.

In total, almost 30 out of the 40 original pieces have survived. Twelve pieces are preserved in museums: three belong to the collections of the Breguet Museum, five are kept in the British Museum and other museums in England, the other ones can be found in Italy, Jerusalem, and New York. A further fifteen are in the hands of private collectors, and in recent years, two pieces were bought at auction.

Despite its success Breguet’s own fascination with his invention was relatively short-lived. His never-ending quest to further improve the precision of timepieces saw him move onto other ideas and projects. Leaving the tourbillon to largely fade into obscurity over tim, although it never disappeared completely. Rather it slumbered, waiting for the right moment to be rediscovered and reintroduced to aficionados the world over.

The Revival

The revival, when it came at last, was as swift as it was unexpected. Although designed for pocket watches, which were generally worn upright, Abraham-Louis Breguet’s invention made its comeback in the mid-1980s, ironically in the much smaller cases of wristwatches that were far less sensitive to gravity. Since then, the triumph of the Tourbillon has proved unstoppable, and year by year, it gains ground. Today, the main advantage of the Tourbillon no longer lies in increased precision. Instead, the enlightened amateur may delight in the beauty of a brilliant invention, in a chapter of human history and in the reassuring regularity of a revolutionary process (in every sense of the word) which, 220 years later, continues to bear witness to the human spirit.

Rolex

Rolex A. Lange & Söhne

A. Lange & Söhne Blancpain

Blancpain Breguet

Breguet Breitling

Breitling Cartier

Cartier Hublot

Hublot Vacheron Constantin

Vacheron Constantin IWC Schaffhausen

IWC Schaffhausen Jaeger-LeCoultre

Jaeger-LeCoultre OMEGA

OMEGA Panerai

Panerai Roger Dubuis

Roger Dubuis TAG Heuer

TAG Heuer Tudor

Tudor FOPE

FOPE Agresti

Agresti L’Épée 1839

L’Épée 1839