The History of Breguet Part. 2: The Inventions of Abraham-Louis Breguet

In Part 1 of our in-depth series on the History of Breguet, we profiled the brand’s founder and namesake, Abraham-Louis Breguet (Breguet), widely considered to be one of the most important and influential figures in watchmaking. (Click here to read that article.) The Swiss-French master watchmaker was a pioneer in just about every sense of the word. It’s true he was not the first, nor the only, to conceive the idea of reforming the design of watch movements for the transition to smaller timepieces. However, it was his vision, ingenuity, and, above all else, passion, that led him to develop solutions that contributed great gains in accuracy, workings, and robustness. In doing so, his work earned him an international reputation second to none in the history of watchmaking. Such is the importance of these contributions to the evolution of watchmaking itself that they deserve, nay demand, their own separate chapter. That is why Part 2 in our in-depth series on the History of Breguet is devoted to the most celebrated inventions of Abraham-Louis Breguet that significantly propelled the development of mechanical watches forward. We invite you to keep reading to learn more about this truly fascinating individual.

1780 – The “Perpétuelle” watch

Objective: A watch that winds itself

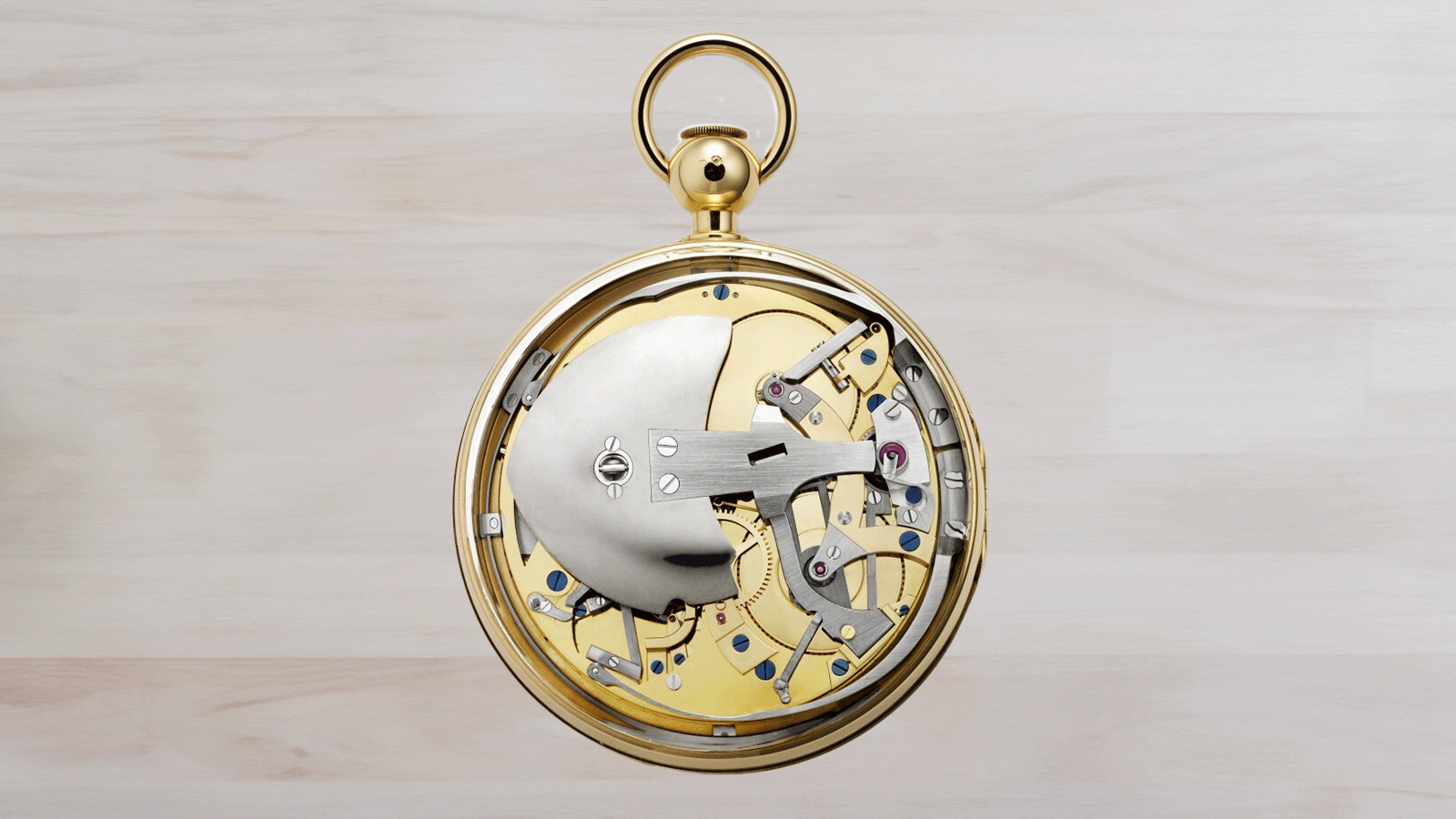

Simple in concept yet ambitious in execution. Not alone in attempting to accomplish the feat, Monsieur Breguet became the first to develop a method by which a reliable automatic watch could be produced. His system employed an oscillating weight that responded to the wearer’s movements (namely walking). Sprung so that it returned to its original position after each movement, the oscillating weight jumped up and down around a pivoting arm. Pushing up two going barrels to wind the mainspring and stopping when the spring was fully depressed.

Perhaps already coined to describe the concept, the term “perpétuelle” was assigned to watches featuring the system. This invention marked the first major success in A-L Breguet’s career. The first perpétuelle was sold in 1780 to the Duc d’Orléans. From then on, his “self-winding watches” brought considerable fame at home and throughout Europe. It’s estimated as many as 90 examples were made and sold by the time of A-L Breguet’s death in 1823. The watch of King’s par excellence remains one of the most powerful symbols of the inventive genius he possessed.

1783 – “Breguet hands”

Objective: Aesthetics in the service of functionality

Hand-in-hand with improving the internal mechanisms Breguet gave much attention to streamlining the external forms of his watches. Indeed, Breguet pocket watches set a precedent. Perhaps the most distinguishing feature, which remains a signature of the brand to this day, was the eccentric type of hand he invented. At the time, watch hands were generally short, broad, and elaborately decorated. The difficulty they presented in reading the time clearly and easily reflected the lack of emphasis on precision common in watchmaking at the time.

Initially, like many of his peers, Breguet used gold English hands for his timepieces, but circa 1783, he took the bold step of inventing something uncompromisingly new. Made of gold or blued steel, the points were hollowed out resembling a crescent moon. Delicate and bestowed with a simple elegance, the new hands improved legibility immediately. The fabrication of these fell to a select group of makers, true artists whom Breguet entrusted with commissions. From then on, the Breguet style of hands, or simply “Breguet hands”, as they are known became widely adopted, remaining popular to this day.

1790 – The Pare-chute

Objective: Protect the pivots of a balance in the event of a shock (or knock) to the watch

Breguet observed that when a watch movement was subject to impact, such as knocking against something, or in the case of a pocket watch, falling out of someone’s pocket, the pivots of the movement’s balance were the most vulnerable. To counter the effects of knocks, Breguet devised a cone-shaped form for his pivots. These in turn were held in place with small dishes of matching shapes, mounted on a strip spring. The invention, which he started testing circa 1790, made his watches infinitely less fragile. Having perfected the “pare-chute” as it became known, Breguet is said to have flung his watch to the floor during a gathering. (At the home of the minister of foreign affairs, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand.) After passing it around, all present had to admit the watch was still in good running order.

From 1792, Breguet perpétuelle watches were all equipped with the pare-chute. Soon after, all Breguet watches carried the new protection system. A definitive version was presented at the National Exhibition of Industrial Products, held in Paris, in 1806. Sometimes called the ‘elastic suspension’ of the balance wheel, the pare-chute was the precursor to the modern “Incabloc” and all other shock protection. The success of the invention enhanced the reputation of Breguet watches even further.

1795 – The “Breguet overcoil” balance-spring

Objective: to permit the balance-spring to ‘breathe’ isochronously (at equal intervals)

A balance spring works by being attached at its ends, leaving the rest of the coil to pulsate. The inner extremity attaches to the axis of the balance, and the elasticity of the spring regulates the oscillations. The flat balance-spring was invented by the Dutch mathematician, Christiaan Huygens, in 1675. It established a rate as accurate as the pendulum. However, this degree of isochronism left something wanting. To attach its outer extremity (to the cock) requires a length of the outermost coil to be held rigid (between the stud and regulating pins). This portion of the spiral’s circumference (almost one-half) is thus not permitted to breathe in and out like the rest.

In 1795, to solve the problem, Breguet upraised the last coil and bent a length back towards the centre of the spring. With the ‘terminal curve’ attached at a location above and within the circumference of the geometry, the spiral section became free to breathe concentrically at all points. Watch movements equipped with the “Breguet Overcoil”, gained in precision (and the balance staff eroded less quickly). Breguet also perfected a bimetallic compensation bar. To cancel out the effects of changes in temperature on the balance-spring. Adopted by all the great watchmaking firms, the “Breguet Overcoil” continues to be used to this day for high-precision pieces.

1801 – The “Tourbillon”

Observation: Gravity is the enemy of the regularity of horological movements

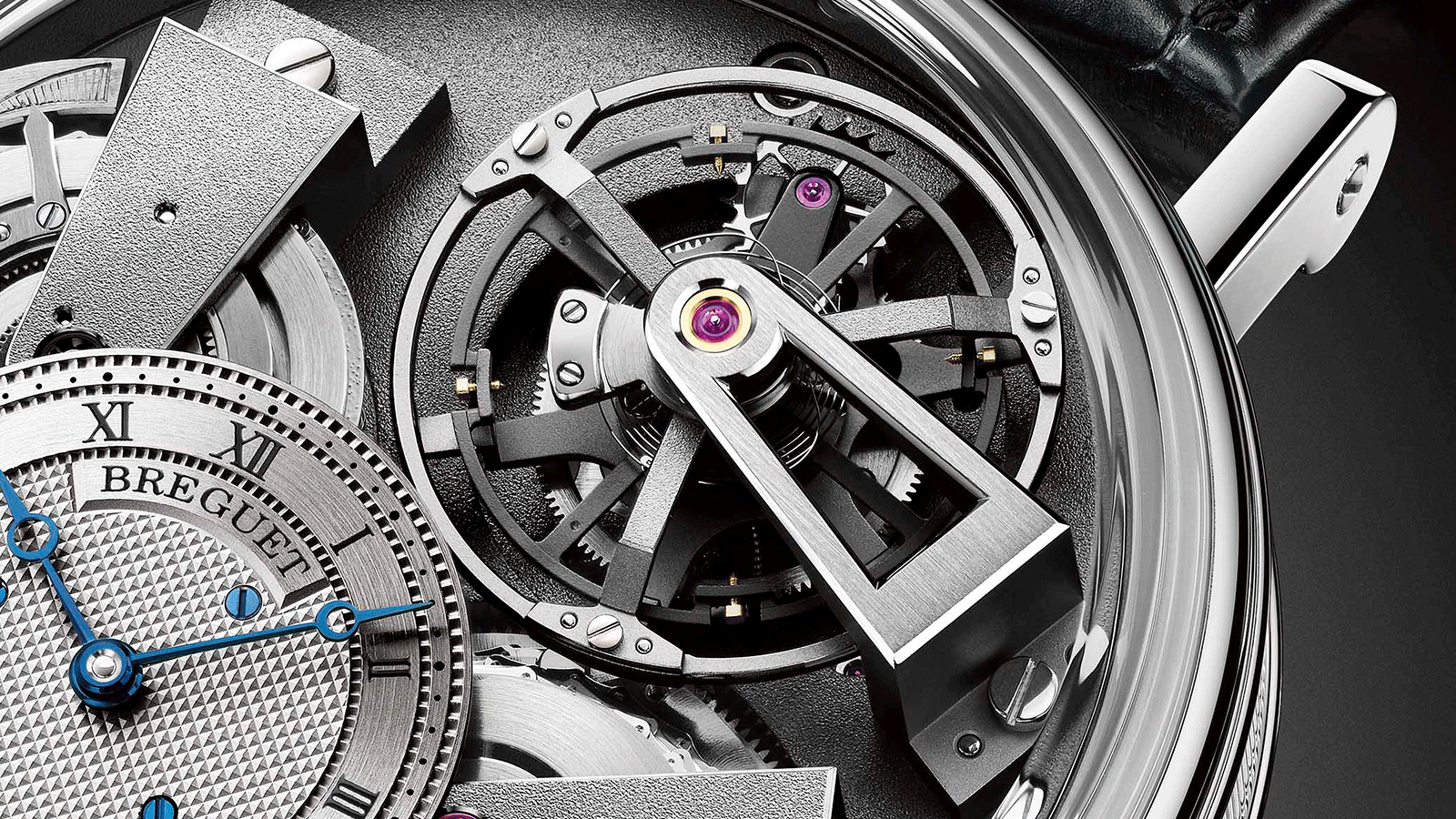

Recall that in Breguet’s time, the order of the day was pocket watches, and these remained in whatever orientation they were placed throughout the day. With each change of position, gravity would provoke variations in timing adjustments. Not being able to eliminate gravity, Breguet set out to distribute its effect evenly. His idea was to install the entire escapement (balance and spring, lever and escape wheel) within a mobile carriage that completes a rotation every minute. By having all flaws repeated regularly, they engaged in a process of mutual compensation. Breguet patented his invention as a new type of regulator called “Tourbillon”.

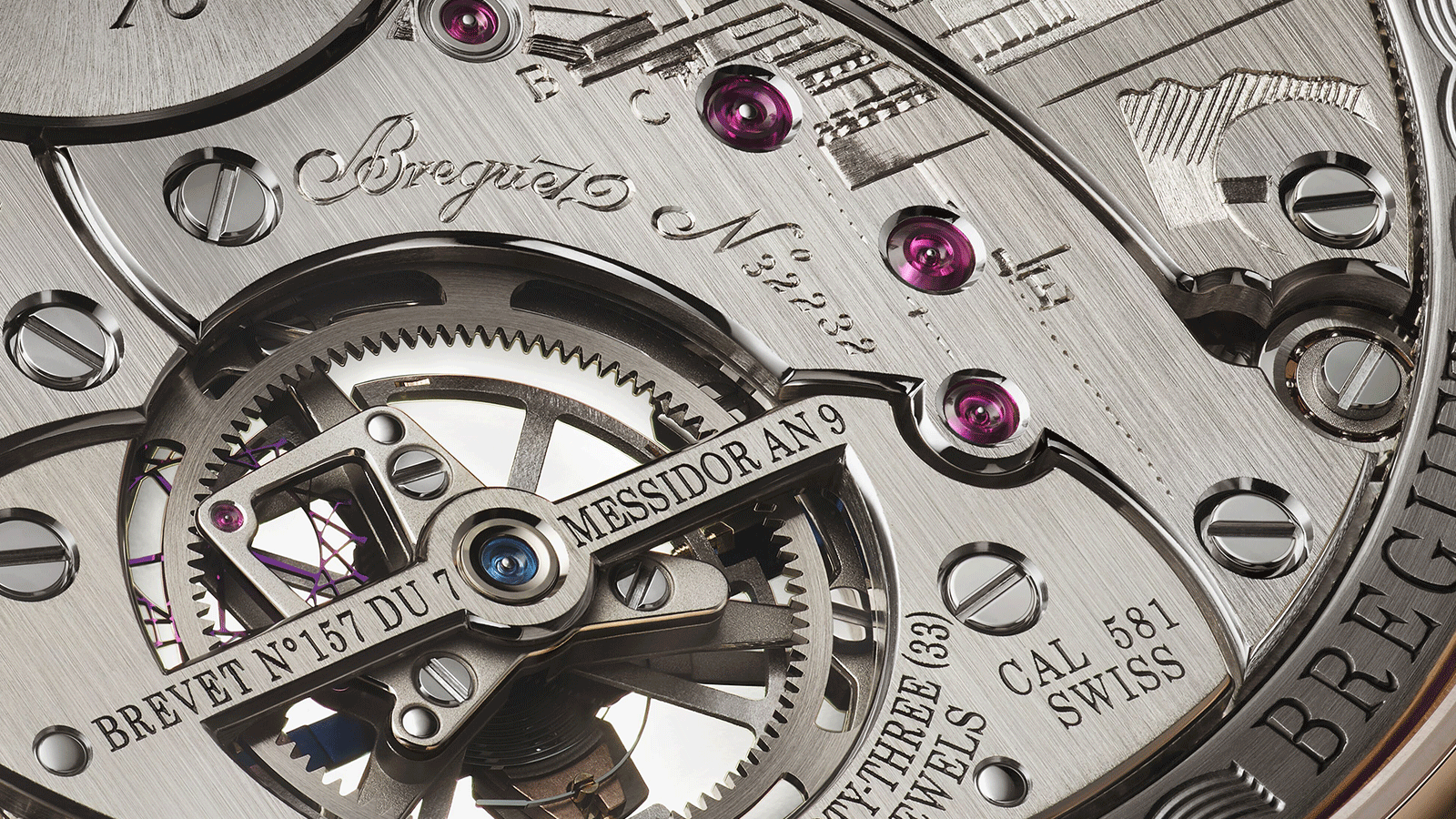

The date of the 10-year patent, 7 Messidor, year IX on the French Republican calendar corresponds to 26 June 1801. Based on a principle that was brilliant and yet extremely complex to produce, the Tourbillon was far from operational at the time. The first was not commercialised until 1805. The following year, the invention was presented at the National Exhibition, described as a mechanism by which timepieces “maintain the same accuracy, whatever the vertical or inclined position of the watch”. The Tourbillon was a constant source of fascination thereafter. A complicated solution for what progress has now achieved via more classic methods. The Tourbillon remains a legendary feather in Breguet’s inventions cap.

Breguet’s Inventions In Action

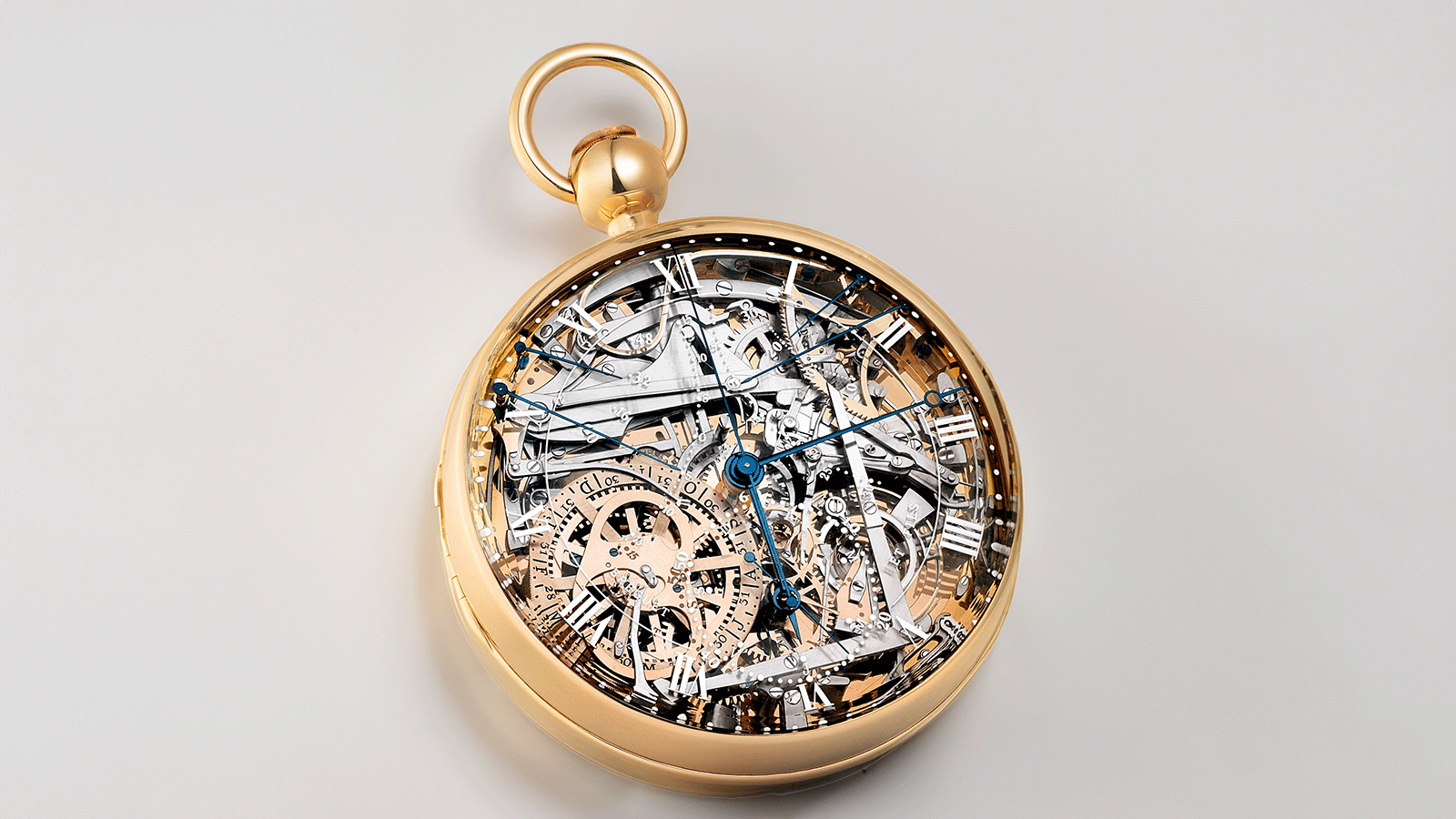

Perhaps one of the best-known examples of Breguet’s inventiveness is number 160. Known as the “Marie-Antoinette”, it was commissioned by an admirer of its namesake in 1783. The gift was requested to be as spectacular as possible, incorporating the fullest range of horological expertise known at the time. Self-winding, it featured a double pare-chute, Breguet hands, and another of Breguet’s inventions, a gong-spring (for chiming). The sophisticated design extends to a special escapement with a natural lift. A cylindrical balance-spring (in gold) and a bimetallic balance.

Marie-Antoinette’s functions consisted of hours, minutes, seconds, perpetual calendar, equation of time, repetition for hours, quarters, and minutes, independent seconds (forerunner to the chronograph hand), thermometer, and 48-hour power-reserve indicator. Not completed until after the Queen’s death, the Grand Complication took on a story all of its own. It should be mentioned that in addition to quality pocket watches, and indeed inventing the first wristwatch, Breguet’s career also included the development of scientific clocks. Particularly marine chronometers for the French Royal Navy. His contribution to horology cannot be understated.

Join us for part three of our series on the History of Breguet, where we will turn our attention to the modern-day Breguet Manufacture.

Rolex

Rolex Blancpain

Blancpain Breguet

Breguet Breitling

Breitling Cartier

Cartier Hublot

Hublot Vacheron Constantin

Vacheron Constantin IWC Schaffhausen

IWC Schaffhausen Jaeger-LeCoultre

Jaeger-LeCoultre OMEGA

OMEGA Panerai

Panerai Roger Dubuis

Roger Dubuis TAG Heuer

TAG Heuer Tudor

Tudor FOPE

FOPE Agresti

Agresti L’Épée 1839

L’Épée 1839 Scatola

Scatola